Enrico Schaefer - November 11, 2020 - Airbnb, Airbnb Refund Claims, Class Action Attorneys, Complex Litigation

The Players: Airbnb, Inc., Airbnb Payments, Inc, and Airbnb Payments UK Ltd. (collectively “Airbnb”), operating through Airbnb.com, is a software platform acting as a ‘directory’ of short-term rental listings posted by its users (“hosts”). Listings added to the directory by hosts are organized by location and are shown to travelers looking for alternatives to hotels and resorts. Travelers can use the Airbnb search feature of the website to locate and book short term rentals (“STRs”) with hosts. Travelers locate properties primarily through a search feature filtered by the host cancellation policy, the traveler’s selected destination, travel dates, the ‘star’ rating of the host, and potential “Super Host’ classification of the host.

Airbnb Hosts have filed class action litigation against Airbnb, Inc and Airbnb Payments, Inc. in California seeking monetary damages and injunctive relief.

STR hosts who chose Airbnb make a substantial investment in the platform, building a body of reviews, building 5-star reviews, developing their reputation, SEO, and status with the Airbnb listing algorithm. Airbnb hosts rely on their ability to control their rental terms within the Airbnb platform to build their STR business. The opportunity cost of moving to another platform is tremendous. Many STR hosts rely on predictable and stable cash flow in order to make mortgage payments, pay cleaning staff, pay support staff, and generate profits.

STR hosts on the Airbnb platform take all the financial risk, purchase properties or offer their own homes or rooms for rent, take out mortgages, do the cleaning and maintenance or hire cleaning and maintenance crews, engage in property management and work hard for ‘5 star’ customer reviews from their guests. STR platforms, including Airbnb, allow the STR host and their guest to enter into short term rental agreements, enforceable under contract law, set the rental terms and house policies and control their cancellation policy to create predictable cash flow.

All STR platforms, including Airbnb, require everyone to agree that they are not parties to the rental agreement in order to avoid liability and local regulations.

Use of Airbnb.com allows users to see all listing information and associated web pages under a ‘browser wrap’ arrangement with the terms of service and privacy policies linked in the footer. Hosts who want to add a listing, and travelers who want to reserve a listing, are provided a click wrap agreement; together with other information and are advised they are agreeing to the terms and privacy policies only through the use of hyperlinks as these policies are stored on other than the registration page. Registered users are not provided a ‘scroll wrap’ which would require a user to review the terms as part of actual registration, and no emailing of terms to users occurs as a result of registration. As the drafter of all terms and policies, Airbnb is the only party to be able to ensure that they are clearly written so they can be easily understood, prominently displayed and consistent with their marketing language.

Airbnb.com operates on some simple principles, many of which are fundamental to this dispute and included in its Terms of Service.

a. Airbnb requires hosts and travelers to both acknowledge and agree that it is just an online marketplace where travelers can find hosts, and to hold the host payouts to confirm the reservation is as listed. (TOS; Section 1.1).

b. Airbnb requires hosts and travelers to both acknowledge and agree that Airbnb is not a party to the rental agreement between hosts and their guests, and not responsible for anything related to the reservations made by travelers using the platform. (TOS; Section 1.2).

c. Airbnb requires hosts and travelers to both agree that Airbnb does not own, create, sell, resell, provide, control, manage, offer, deliver, or supply any Listings or Host Services and thus has no involvement in hosting or managing properties. (TOS; Section 1.2).

d. When a traveler makes a reservation with a host, Airbnb, through a wholly owned subsidiary, collects the rental payment and holds the ‘host payout’ in escrow to either apply the cancellation policy agreed to by the guests and controlled by the hosts or disburse to the host on occupancy (TOS; Section 1.2).

e. Airbnb requires hosts and travelers to both acknowledge and agree that the rental agreement is exclusively between hosts and their guests, under the terms selected and controlled by Hosts, including the cancellation policy selected by hosts and the house rules posted with their listing. (TOS; Section 1.2).

f. Airbnb reserves the right to change the terms between Airbnb and its members (hosts and travelers), but only after giving its members thirty days notice by email and only applying those new provisions moving forward after the expiration of 30-days. (TOS; Section 3).

g. Airbnb is simply a software platform and allows the parties (hosts and guests) the freedom to contract and enter into a short term rental agreement on terms controlled by the host.

The very first paragraph of both the Terms of Use and Payment Terms policies, in the most prominent location in the Terms of Use and Payment Terms is Airbnb’s stated and repeated preference for Consumer Arbitration with AAA for ‘all disputes’ by ‘all members’ and the class action waiver by ‘all members. In order to enforce these types of severe limitations on user rights and remedies and to require arbitration in an adhesion contract, Airbnb must provide a clear, fair and efficient alternative to other available dispute resolution forums.

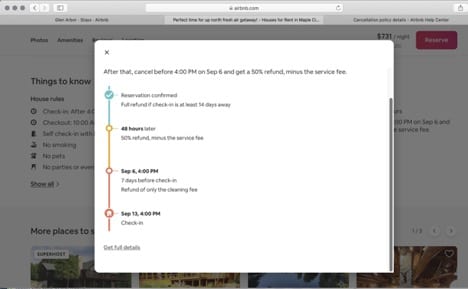

The rental contract between a host and a guest is made at the time the reservation is booked, and the guest clicks the ‘RESERVE’ button and makes payment to the “Airbnb Payments Entity” which acts as an escrow company holding the host payout until check-in by the guest. The rental contract between hosts and their guests include the payment terms, the listing details, the house rules and the host cancellation and refund policy. After a traveler ‘reserves’ the property, the Airbnb platform blocks the listing for the booked reservation dates making it impossible for anyone else to rent the property during the reservation dates and making the property unavailable to any other potential renters. Booking a property is, among other things, a commitment by the traveler to pay, and a commitment by the host to remove the listing availability.

Airbnb acting through its wholly owned subsidiary Airbnb Payments agreed to make payouts to the host consistent with the host mandated cancellation policy (TOS Section 9.2) and Airbnb’s Guest Refund Policy.

Hosts who list their properties on the Airbnb platform ultimately have several options in setting their cancellation policies, generally identified within the platform as flexible, moderate, strict and super strict. The default cancellation policy set and heavily promoted and preferred by Airbnb is ‘flexible’ with free cancellation and a full refund up until 24 hours before check-in as depicted below.

The Airbnb hosts’ sign-up process not only encourages flexible cancellation policies, but automatically designates the initial cancellation policy as flexible. Regardless, Airbnb understands that many hosts need to either place the cancellation risk onto travelers or split the risk with travelers in order to ensure cash flow. Airbnb allows within its platform complete control over cancellation policy selection by hosts. Hosts must search within their set-up options to change the cancellation policy from flexible to some other option. Airbnb generally shows listings with flexible and moderate cancellation policies before listings with strict and super strict cancellation policies and continually markets to hosts to change their cancellation policies to flexible. Hosts are told that stricter cancellation and refund policies will negatively impact their listings search results and are made to agree by clicking several checkboxes that they understand the negative consequences of using a stricter cancellation and refund policy. Regardless of Airbnb’s preference for less restrictive cancellation policies, Airbnb provides ‘choice’ and ‘control’ to hosts in order to promote the use of their platform by hosts.

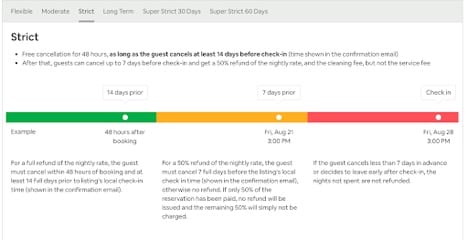

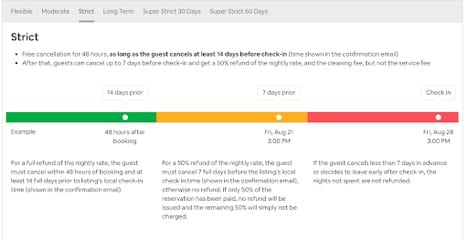

Because of the importance of cash flow for many hosts, many hosts including this claimant select a “strict’or ‘super-strict’ cancellation policy. A depiction by Airbnb of the current strict cancellation and refund policy and super-strict cancellation and refund policy are shown below.

When a traveler is searching for properties, the traveler can filter out all properties with strict cancellation policies as a top line, top left filter item.

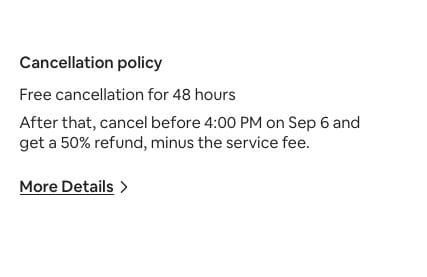

Travelers see the cancellation policy of hosts in several places before reserving the property, and even for strict cancellation policies are afforded a 48 hour grace period to cancel a reservation for a full refund if they decide they are not comfortable with a cancellation policy, or any other aspect of the listing or rental agreement.

Representative images of the selection and agreement by the traveler to the host cancellation policy are shown below:

Airbnb has an entire policy page devoted to refunds titled “Airbnb Guest Refund Policy.” Guests are told they can only get refunds if there is a host created “Travel Issue” which is defined as host cancellation, or a “listing’s description or depiction of the accommodation is materially inaccurate” or when the house is uninhabitable because of, for instance, vermin or undisclosed pets. The “Airbnb Guest Refund Policy” has mandated a detailed procedure for the guest and Airbnb before a refund as a result of a host-created problem can be processed. Regardless, none of the Airbnb Guest Refund Policies would support a refund in bookings at issue in this matter. The guests in this case agreed to the Claimant’s strict (or super-strict) cancellation policy.

36. It is important to understand the context in which Airbnb is made and continues to make decisions, including:

a. refund decisions,

b. its cavalier attitude towards its obligations under the various terms and policies, and

c. its shift towards using its escrow role to benefit itself using host pay-outs for its own business or converting those payouts into Airbnb revenue.

As the COVID-19 epidemic, soon to be pandemic, started sweeping through China, the far east and Europe, Airbnb was on the cusp of a highly publicized Initial Public Offering (IPO). It was expected the public offering would be made in May 2020. Airbnb’s primary focus in the winter and early Spring of 2020 was on increasing its IPO valuation.

In preparation for its IPO, Airbnb calculated the value of a ‘traveler’ in comparison to the value of a ‘host’ concluding that travelers were far more valuable. Airbnb concluded that hosts would be incentivized to use the platform as long as Airbnb was able to attract an increasing number of travelers and remain the market leader against its hard charging competition, namely booking.com and VRBO. Upon information and belief, Airbnb decision-making related to cancellations, security deposits, damage to properties caused by travelers, and other customer support issues began to skew heavily towards keeping travelers happy, irrespective of the Terms of Service and host cancellation policies.

Airbnb is divided into divisions, one of which is the traveler division, and another is the host division. The traveler division received financial and other resources, had more power in decision making and was provided a preference over the host division as Airbnb approached its expected IPO. Airbnb in the shadow of an IPO seemed increasingly detached from its obligations to hosts, or the fact that Airbnb’s success was built on the backs of hosts.

Airbnb was aware of COVID-19 well before most governments, including the United States, as a result of its Global presence and specifically via extensive presence and listings in China, including Wuhan, China. Airbnb began making calculated decisions about how COVID-19 would impact its upcoming IPO, how to retain travelers and how to maximize its value for a delayed IPO if necessary. Airbnb began making calculated decisions to gain for itself a competitive advantage over companies like booking.com and VRBO as a result of COVID-19’s negative impact on all travel. Airbnb decided that it would delay its IPO and focus its efforts to ensure that travelers would return to Airbnb after the COVID-19 impact on travel started to soften.

Airbnb decided that it would seek to reform the existing rental agreements between hosts and their guests by creating a new policy specific to COVID-19 to justify its decision to provide refunds to travelers, and override the strict and super-strict cancellation policies of hosts. Airbnb’s public relations team sought to divert over $1 Billion dollars in payouts belonging to hosts for its own public relations benefit and goodwill valuation, and convert over $500 million dollars of host payouts into revenue for Airbnb through a bogus ‘travel credit’ strategy (see Travel Credit Scam below). Airbnb further decided it would keep all Airbnb fees for cancelled reservations.

Airbnb created a new web page indicating that the existing Extenuating Circumstances Policy (ECP) did not apply to COVID-19 refund claims, specifically noting “[The extenuating Circumstances Policy] does not address circumstances related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.” Instead, on or about March 1, 2020, Airbnb created and expressed its intention to apply a newly created “COVID-19 policy.” The way back machine shows 110 captures and ~50 changes since March 14, 2020, none of which were changed pursuant to 30 days email notice under Section 3 of the TOS. Airbnb’s new “COVID-19 ECP” was sent to travelers with reservations, explaining that they could obtain a full refund if they cancelled before check-in, minus Airbnb’s fees, all without question, vetting, documentation or support as would have been required under its prior policies The new COVID-19 ECP was put into effect without the required 30-day email notice to hosts required to become effective under their take it or leave it policies. The new COVID-19 ECP was applied retroactively to existing reservations against the express provisions of the Terms of Service which provide in Section 3 that no changes can become effective until after the (30) day email notice is sent to users.

Despite all parties, including and especially Airbnb, having agreed in the TOS that Airbnb was not involved in any way with listing including hosting or managing properties, Airbnb sought to insert itself directly into the most important hosting and property management function; namely, customer service, refunds, and cancellations. Hosts almost immediately became irate for a variety of reasons, including:

a. Hosts had not been provided any input or notice of Airbnb’s unilateral decision to communicate directly with the hosts’ guests encouraging and causing full refunds, and ultimately bogus travel credits (see Travel Credit Scam below).

b. Hosts were already working things out with guests, including in some instances offering partial refunds that travelers were not entitled to under the cancellation policy and their own travel credits for future travel.

c. Many travelers had previously agreed with hosts to cancel right away so that the listing calendars would open so other travelers could book reservations, some of which was still occurring, including emergency workers, business travel and local travel. Airbnb’s communication to travelers encouraged them to wait until the last minute to cancel, blocking host calendars until just before the booking.

d. Many locations had no travel issues or COVID-19 issues during the applicable time periods of the COVID-19 ECP.

e. Many guests had already indicated that they were cancelling because conferences had been canceled or for other personal reasons, which could never be a valid reason for a refund under any Airbnb policy.

f. Hosts in some cases had agreed to provide refunds to guests if the host was able to rebook. Airbnb interfered with those rental agreement modifications between hosts and guests.

g. Airbnb’s new policy allowed, and thereby encouraged, travelers to wait before cancelling.

h. Airbnb’s new policy, and its communications with travelers were generally hostile to hosts, undermined the hosts, their customer relationships and adversely affected their reputations. Airbnb’s customer support personnel pressured hosts to consent to refunds by telling guests things like:

i. ‘Most hosts are offering refunds,’ when in fact many hosts had flexible or moderate cancellation policies which provided for full refunds under their rental contracts, Airbnb had forced refunds on hosts with strict cancellation policies and Airbnb used other deceptive tactics to pressure hosts.

ii. Failing to support and undermine hosts who had already told guests that the strict cancellation policy they had agreed to did not provide a refund or were already providing options to guests.

iii. Telling guests they could get a full refund even after guests had agreed to abide by their cancellation policy.

i. Airbnb’s handling of the matter made it far less likely that travelers would book again with the host in the future.

j. Airbnb’s decision to interfere with the cancellation policy of hosts, many of whom had multiple properties, created unexpected cash flow issues and resulted in significant loss of revenue. Hosts had relied on their cancellation policies and general 50-50 split of the reservation fee with their guests in order to navigate issues created by COVID-19 and endure the pandemic.

k. Airbnb’s unilateral actions made it difficult for hosts to pay the workers supporting their STR operations, including cleaning and maintenance crews, pay mortgages and satisfy other obligations.

l. Hosts are not offered any insurance options through the Airbnb platform for unexpected events. Travelers have the option to buy ‘traveler insurance’ including all-risk policies which would cover pandemics. Many hosts had fully advised their guests to purchase traveler insurance as part of the booking process.

m. While COVID-19 was hard on everyone, there was nothing inherently unfair about splitting the pandemic risk 50-50 in most cases, as previously agreed by hosts and guests under a strict cancellation policy.

n. While Airbnb was telling hosts that refunds were justified irrespective of their cancellation policies because no one could have foreseen the COVID-19 Pandemic, Airbnb was telling travelers not to expect their more basic traveler insurance to provide coverage since pandemics were expected events.

The ECP is contrary and/or inconsistent with the Guest Refund Policy which only provides refunds if a host cancels or a house is substantially uninhabitable as compared to the listing details.

a. Prior to March 1, 2020 or so, Airbnb’s ECP purported to allow a refund after review by a specialized team and ensuring the traveler was ‘directly affected’ in extremely limited circumstances, if the hosts or a guest suffered an endemic disease. However, this EPC provision was extremely limited in that a guest, or their travelling party, could only make a request for refund if the endemic was not associated with an area; meaning the endemic could not be something that an area had experienced previously … “for example, malaria in Thailand or dengue fever in Hawaii [would not be an extenuating circumstance].” So, for instance, malaria as a localized disease, would only be the subject of a possible refund if it took hold in another unexpected geographic area such as London, and did not become an epidemic or pandemic, but malaria would not be the cause of a possible refund in Thailand.

b. Neither epidemics or pandemics were included by Airbnb or its attorneys in drafting the original ECP which, assuming it is even valid, would have been the version in effect at the time of most of the subject reservations in this case.

c. An ‘endemic’ is fundamentally different from an ‘epidemic’ or a larger epidemic called a ‘pandemic.’ See https://bit.ly/3g7R9qY. (What’s the difference between epidemic and endemic? An epidemic is actively spreading; new cases of the disease substantially exceed what is expected. More broadly, it’s used to describe any problem that’s out of control, such as “the opioid epidemic.” An epidemic is often localized to a region, but the number of those infected in that region is significantly higher than normal. For example, when COVID-19 was limited to Wuhan, China, it was an epidemic. The geographic spread turned it into a pandemic. Endemics, on the other hand, are a constant presence in a specific location. Malaria is endemic to parts of Africa. Ice is endemic to Antarctica.)

i. An EPIDEMIC is a disease that affects a large number of people within a community, population, or region.

ii. A PANDEMIC is an epidemic that’s spread over multiple countries or continents.

iii. An ENDEMIC is something that belongs to a particular person or country.

A lawyer drafting the adhesion TOS for Airbnb would never have included the word ‘endemic’ without having decided to intentionally exclude ‘epidemics’ and ‘pandemics’. Airbnb and its attorney specifically sought and decided to exclude pandemics from inclusion of the ECP in effect at the time of the subject reservations. On or about March 1, 2020, Airbnb secretly and without the required 30 day notice under Section 3 of the TOS changed the word ‘endemic’ to ‘epidemic’ in its ECP, and tried to hide that change from the world, including deleting the pre-March 13 version of the ECP from its website, and scrubbing its website of all references to the word ‘endemic.’

Airbnb then misrepresented that its ECP had always included the word ‘epidemic’ and allowed its lawyers to argue that Airbnb was merely clarifying the ECP policy.

Airbnb makes money by charging a service fee — a percentage of the total — to both the people who rent out their space (hosts) and those who stay there (guests). By connecting travelers and hosts through its directory of listings, Airbnb makes billions of dollars per year from hosts offering short term rentals on its platform.

After Airbnb made its unilateral decision to interfere with host refund policies and ignore its own contract obligations, Airbnb:

a. went on a public relations tour taking credit for refunding guests, creating the impression that Airbnb had refunded travelers, when in fact, the refunds were provided exclusively by host payouts converted by Airbnb.

b. Airbnb essentially used over one billion dollars in host payouts to purchase one billion dollars of goodwill from travelers.

c. In fact, Airbnb did not refund travelers but aggressively pushed ‘Airbnb travel credits’ on travelers. Airbnb used a variety of techniques to avoid refunds to travelers, including user messaging and flow which made it easy for a guest to claim travel credits and difficult for guests to obtain refunds.

d. Upon information and belief, many guests did not know they could obtain a refund, and believed their only option was an Airbnb travel credit good only for one year.

e. According to Airbnb over $500,000 million worth of travel credits were issued to travelers, many of whom never realized they could obtain a refund. Who would take a travel credit over a full refund?

f. Airbnb knows that people receiving travel credits often don’t use them, forfeiting the money. Upon information and belief, Airbnb used the travel credit scam for the specific purpose of converting host pay-outs – to which Airbnb could never have any claim – into Airbnb revenue.

g. It is unclear whether the host pay-outs, now represented as Airbnb travel credits, have already been moved into Airbnb’s general accounts in order to relieve its cash flow problems and improve its IPO balance sheet.

Airbnb disregarded its own initial ECP, and its revised ECP, in refunding guests who were cancelling for reasons having nothing to do with personal health issues, for instance providing full refunds to travelers who cancelled before the new COVID ECP, who were outside the dates set forth in the COVID ECP and who admitted that they were cancelling for reasons not covered by any version of the ECP. Even if the word pandemic had been included in the applicable ECP, Airbnb would not have been entitled to avoid its own contractual obligations and review process. Airbnb would not have been entitled to incite guests and encourage cancellations. Airbnb would not have been entitled to interfere with the efforts of hosts to manage their customer relationships. Under Airbnb’s interpretation of the ECP, it does not have to provide any justification for ECP refunds, is not accountable to hosts to show it went through the required process, and does not need to show its own communications with the hosts’ guests requesting a full refund.

As an escrow for host payouts, Airbnb has no right to unilaterally, in its sole discretion, for any reason, and without justification, interfere with a cancellation policy agreed to between hosts and their guests. The ECP is a fraudulent scheme by which Airbnb and its escrow service take full control of payouts belonging to hosts and use host payouts for Airbnb’s own purposes.

Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky on or about March 30, 2020 in a YouTube video message to hosts told them that the ‘[ECP] cancellation update’ and decision to refund travelers was ‘not a business decision.’ Discovery will reveal that the decision to refund travelers was in fact a business decision by Airbnb. Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky on or about March 30, 2020 in a YouTube video message to hosts told them that Airbnb had made mistakes, and that the Host’s cancellation policies would be honored moving forward. This proved to be untrue. Airbnb continues, among other things, to offer refunds in violation of the cancellation policies of hosts, change its policies without the 30-day required email notice under Section 3, force hosts to offer refunds, provide misinformation to guests, reform rental agreements, covert host payouts into Airbnb travel credits and interfere with the relationship between hosts and guests.

By way of example only, Airbnb’s new COVID-19 ECP version purports to require guests to ‘attest’ – defined as sworn under oath – that they or someone in their party has COVID-19 before allowing a refund. Upon information and belief, Airbnb is not requiring sworn proof, or any substantial proof, of a COVID-19 diagnosis. In fact, guests in some instances needed only to click a link to receive an Airbnb travel credit or full refund without any review. Airbnb had obligations to review all refunds requests under the TOS, and all versions of the ECP, but admits it did not do so, instead laying off hundreds or thousands of customer personnel and summarily allowing refunds to reduce its own overhead and expenses.

The COVID ECP has been modified numerous times since March 2020, with no contractually required 30-day notice by email to hosts, and ignoring the ECP that would have been in effect at the time the rental contract was entered into between the host and guest. Even modified ECPs were not implemented as drafted by Airbnb. Airbnb’s refusal to implement the rental agreement entered into at the time of the reservation is also demonstrated by their refusal to apply the cancellation policy in effect at the time the rental contract was entered into between the host and guest. For instance, the Strict cancellation policy was changed in or about December 2019 from 14 days to 7 days from check-in date. Even for cancellations having nothing to do with COVID, Airbnb provided a full refund to travelers cancelling between 7 and 14 days, when they should have received no refund at all.

Airbnb violated its terms of services and policies when it unilaterally, without notice and without consent, incited and offered refunds to travelers in direct violation of the cancellation policy agreed to and contracted between host and traveler. Airbnb secretly changed its refund and cancellation policies and then wrongfully applied those policies retroactively to existing reservations and hosting contracts. Airbnb failed to provide notice of TOS changes as required under Section 3 and violated the TOS by then applying modified terms to existing reservations and guest/host rental agreements. Airbnb further sought to defraud hosts and travelers with a newly implemented exceptional circumstances policy and its applicability to COVID-19 cancellations in violation of host cancellation policies. Airbnb failed, under the TOS, to perform the required process for submitting and reviewing exceptional circumstances claims in order to protect its own interest, and against the interest of hosts. A key part of Airbnb’s business model is to hide much of the information hosts would need to know if Airbnb has breached its TOS, the extent of damages and the rationale and support provided by guests for cancellations. By way of example only, Airbnb initially deleted reservation and payout information from Host accounts which would allow a Host to view the payouts and other losses incurred.

Airbnb tortiously interfered with the relationships and existing rental agreements between hosts and travelers to which Airbnb is expressly not a party, as set forth in Section 1.2 of its TOS, causing hosts damages and benefitting Airbnb. Airbnb customer service personnel are providing guests misinformation about host cancellation policies, traveler rights under long standing reservation agreements, its own application of policies, and other matters, causing confusion and interfering with these relationships.

Airbnb act as fiduciaries, trustees and/or collection agents holding guest rental payments to ensure the host listing is as represented and available on the day and time indicated in the reservation. Airbnb affirmatively requires both the traveler and the host to agree that Airbnb is NOT a party to the rental agreement between the traveler and the host. Despite acting merely as trustee of rental payouts to Hosts, Airbnb’s attorneys and customer support, through the Extenuating Circumstances Policy (ECP) and Terms, nevertheless take the position that it can unilaterally decide whether to (a) pay hosts, (b) convert the host payout into Airbnb travel credits/revenue or (c) fully refund guests despite the rental agreement which indicated that guest would receive, for example with a strict cancellation policy, a 100% refund within 48 hours of making the reservation, forfeit 50% of their rental fee if cancelled 7 days or earlier before their check-in date or 100% of their rental payment if cancelled within 7 days of the check-in date.

Airbnb misappropriated/converted reservation payouts belonging to hosts, and for which Airbnb was a trustee. By converting pay-outs into travel credits that might never be redeemed, Airbnb took control of payout funds belonging to hosts which could never belong to Airbnb, but for Airbnb’s benefit. Airbnb used host payouts to mitigate its own losses as a result of COVID-19, attract additional investment and position itself for its IPO. Airbnb sought to retroactively make hosts the ‘insurer’ of the pandemic in order to protect travel insurance companies, credit card companies, itself and other third parties with whom Airbnb has its own relationships beneficial to Airbnb.

Airbnb customer service personnel are providing guests misinformation about host cancellation policies, traveler rights under long standing reservation agreements, its own application of policies and other matters. Airbnb is representing to travelers that their travel insurance ‘may not’ apply to COVID-19 cancellations because the “COVID-19 pandemic is an ‘expected event’” yet telling hosts that full refunds are appropriate despite the terms of service because COVID-19 was an unexpected event. Airbnb’s website and marketing process, emails and web pages are often inconsistent with Airbnb’s TOS. This includes Airbnb’s representations to hosts when they register to use the site that they control their cancellation policy and thus cash flow and risk, but then Airbnb purports in its adhesion browser wrap agreement to reserve the right to override the cancellation policy in its sole discretion for any reason.

Hosts are seeking a declaration that certain terms of the TOS are invalid and unenforceable, as well as equitable relief, including but not limited to the following:

a. Declare that the Consumer Rules apply to this arbitration under the Airbnb Terms.

b. Declare that Airbnb, Inc and Airbnb Payments are subject to arbitration under the terms.

c. Declare that US law applies, and that all terms related to Airbnb Ireland and Irish Law are invalid.

d. Declare the validity/invalidity of contract terms including the ECP.

e. Reform the TOS and Payment Terms to reflect the agreement a reasonable user of the platform would have believed they were accepting by click-wrap, given the language in the terms and policies, and marketing language from the website taking all ambiguities, inconsistencies and misrepresentations in favor of the platform user.

f. Order injunctive relief, specific performance and other equitable relief precluding Airbnb from refunding customers under all or parts of the ECP.

g. Order injunctive relief, specific performance and other equitable relief requiring Airbnb to comply with the notice requirements under Section 3 to provide email notice of all changes to TOS or related policies, to provide all versions of Terms Service pre and post change and provide a viable and equitable process for accepting and rejecting changes to the TOS and related policies.

h. Order an equitable accounting for profits from the gains that Airbnb benefited from Airbnb’s breach of fiduciary duty and other wrongs.

i. Order Airbnb all evidence and Customer Support emails related to cancellations and refunds so that Claimant can understand their rights and potential breaches by Airbnb.